In this chapter we will learn how to manipulate and summarise data using the dplyr package (with a little help from the tidyr package too).

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, learners should be able to:

Use the pipe (%>%) to chain multiple functions together

Design chains of dplyr functions to manipulate data frames

Understand how to identify and handle missing values in a data frame

Both dplyr and tidyr are contained within the tidyverse (along with readr) so we can load all of these packages at once using library(tidyverse):

# don't forget to load tidyverse!library(tidyverse)

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.2 ✔ tibble 3.3.0

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.1.0

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errors

2.1 Chaining functions together with pipes

Pipes are a powerful feature of the tidyverse that allow you to chain multiple functions together. Pipes are useful because they allow you to break down complex operations into smaller steps that are easier to read and understand.

What do you think this code does? It calculates the mean of my_vector, rounds the result to the nearest whole number, and then converts the result to a character. But the code is a bit hard to read because you have to start from the inside of the brackets and work your way out.

Instead, we can use the pipe operator (%>%) to chain these functions together in a more readable way:

See how the code reads naturally from left to right? You can think of the pipe as being like the phrase “and then”. Here, we’re telling R: “Take my_vector, and then calculate the mean, and then round the result, and then convert it to a character.”

You’ll notice that we didn’t need to specify the input to each function. That’s because the pipe automatically passes the output of the previous function as the first input to the next function. We can still specify additional arguments to each function if we need to. For example, if we wanted to round the mean to 2 decimal places, we could do this:

R is clever enough to know that the first argument to round() is still the output of mean(), even though we’ve now specified the digits argument.

Plenty of pipes

There is another style of pipe in R, called the ‘base R pipe’ |>, which is available in R version 4.1.0 and later. The base R pipe works in a similar way to the magrittr pipe (%>%) that we use in this course, but it is not as flexible. We recommend using the magrittr pipe for now.

To type the pipe operator more easily, you can use the keyboard shortcut Cmd-shift-MCmd-shift-M (although once you get used to it, you might find it easier to type %>% manually).

Practice exercises

Try these practice questions to test your understanding

1. What is NOT a valid way to re-write the following code using the pipe operator: round(sqrt(sum(1:10)), 1). If you’re not sure, try running the different options in the console to see which one gives the same answer.

✗1:10 %>% sum() %>% sqrt() %>% round(1)

✔sum(1:10) %>% sqrt(1) %>% round()

✗1:10 %>% sum() %>% sqrt() %>% round(digits = 1)

✗sum(1:10) %>% sqrt() %>% round(digits = 1)

2. What is the output of the following code? letters %>% head() %>% toupper() Try to guess it before copy-pasting into R.

The invalid option is sum(1:10) %>% sqrt(1) %>% round(). This is because the sqrt() function only takes one argument, so you can’t specify 1 as an argument in addition to what is being piped in from sum(1:10). Note that some options used the pipe to send 1:10 to sum() (like 1:10 %>% sum()), and others just used sum(1:10) directly. Both are valid ways to use the pipe, it’s just a matter of personal preference.

The output of the code letters %>% head() %>% toupper() is "A" "B" "C" "D" "E" "F". The letters vector contains the lowercase alphabet, and the head() function returns the first 6 elements of the vector. Finally, the toupper() function then converts these elements to uppercase.

2.2 Basic data manipulation

To really see the power of the pipe, we will use it together with the dplyr package that provides a set of functions to easily filter, sort, select, modify and summarise data frames. These functions are designed to work well with the pipe, so you can chain them together to create complex data manipulations in a readable format.

For example, even though we haven’t covered the dplyr functions yet, you can probably guess what the following code does:

# use the pipe to chain together our data manipulation stepsm_dose %>%filter(cage_number =="3E") %>%drop_na(weight_lost_g) %>%pull(weight_lost_g) %>%mean()

This code filters the m_dose data frame to only include data from cage 3E, then pulls out the weight_lost_g column, and finally calculates the mean of the values in that column. The first argument to each function is the output of the previous function, and any additional arguments (like the column name in pull()) are specified in the brackets (like round(digits = 2) from the previous example).

We also used the enter key after each pipe %>% to break up the code into multiple lines to make it easier to read. This isn’t required, but is a popular style in the R community, so all the code examples in this chapter will follow this format.

We will now introduce some of the most commonly used dplyr functions for manipulating data frames. To showcase these, we will use the m_dose that we practiced reading in last chapter. This imaginary dataset contains information on the weight lost by different strains of mice after being treated with different doses of MouseZempic®.

# read in the data, like we did in chapter 1m_dose <-read_delim("data/mousezempic_dosage_data.csv")

Rows: 344 Columns: 9

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (4): mouse_strain, cage_number, replicate, sex

dbl (5): weight_lost_g, drug_dose_g, tail_length_mm, initial_weight_g, id_num

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.

Before we start, let’s use what we learned in the previous chapter to take a look at m_dose:

You might also like to use View() to open the data in a separate window and get a closer look.

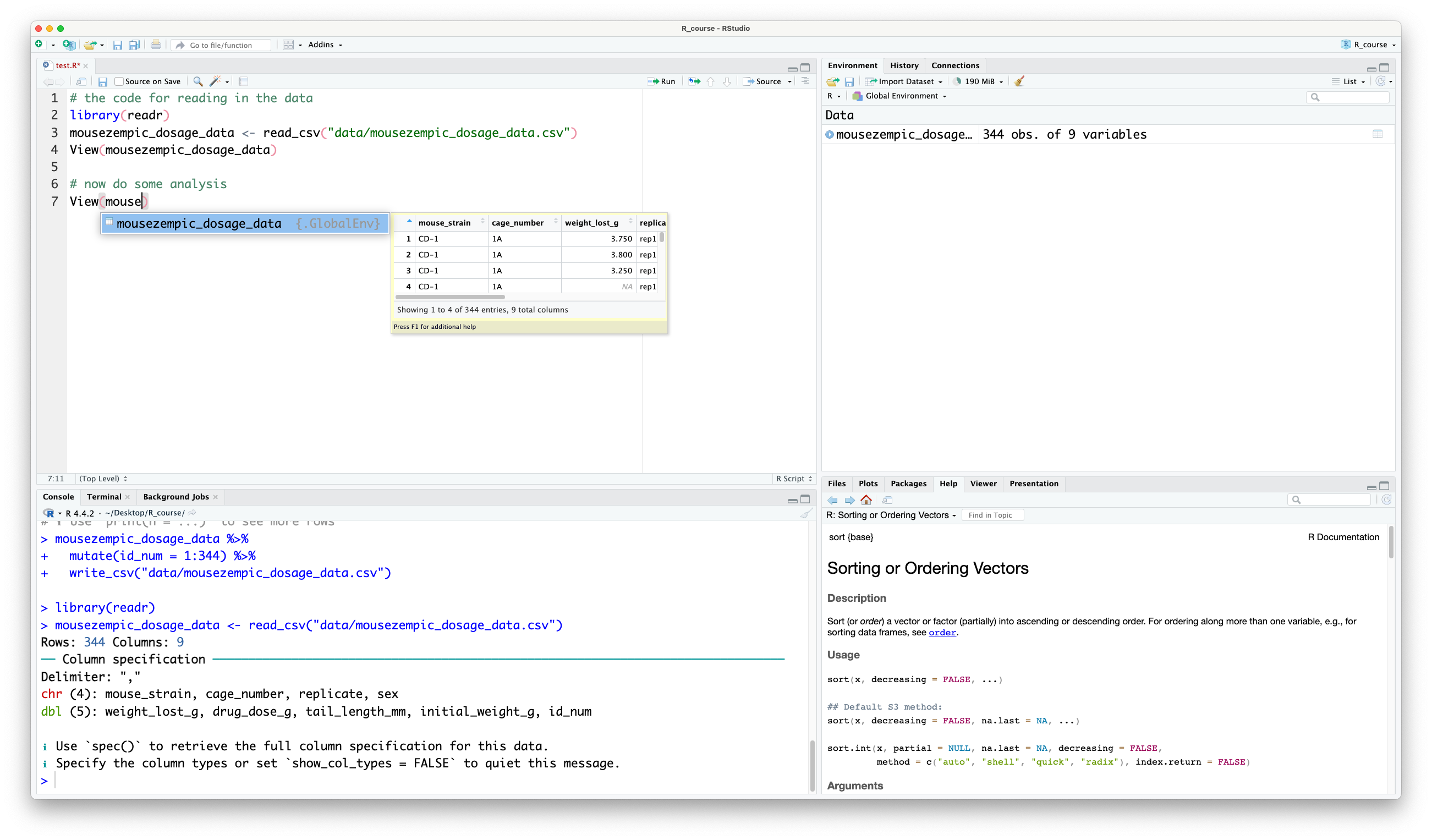

Using RStudio autocomplete

Although it’s great to give our data a descriptive name like m_dose, it can be a bit of a pain to type out every time. Luckily, RStudio has a handy autocomplete feature that can solve this problem. Just start typing the name of the object, and you’ll see it will popup:

RStudio autocomplete

You can then press TabTab to autocomplete it. If there are multiple objects that start with the same letters, you can use the arrow keys to cycle through the options.

Try using autocomplete in this chapter to save yourself some typing!

2.2.1 Sorting data

Often, one of the first things you might want to do with a dataset is sort it. In dplyr, this is called ‘arranging’ and is done with the arrange() function.

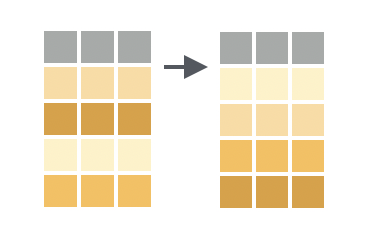

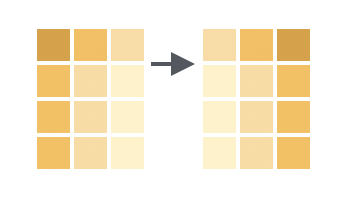

Arrange orders rows by their values in one or more columns

By default, arrange() sorts in ascending order (smallest values first). For example, let’s sort the m_dose data frame by the weight_lost_g column:

If we compare this to when we just printed our data above, we can see that the rows are now sorted so that the mice that lost the least weight are at the top.

Sometimes you might want to sort in descending order instead (largest values first). You can do this by putting the desc() function around your column name, inside arrange():

m_dose %>%# put desc() around the column name to sort in descending orderarrange(desc(weight_lost_g))

# A tibble: 344 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Black 6 3E 6.3 rep1 male 0.00221

2 Black 6 3E 6.05 rep1 male 0.0023

3 Black 6 3E 6 rep2 male 0.0022

4 Black 6 3E 6 rep3 male 0.00222

5 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep2 male 0.00223

6 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep3 male 0.00229

7 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep1 male 0.00213

8 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep1 male 0.00217

9 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep3 male 0.0023

10 Black 6 3E 5.8 rep2 male 0.00229

# ℹ 334 more rows

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

Now we can see the mice that lost the most weight are at the top.

Comments and pipes

Notice how in the previous example we have written a comment in the middle of the pipe chain. This is a good practice to help you remember what each step is doing, especially when you have a long chain of functions, and won’t cause any errors as long as you make sure that the comment is on its own line.

You can also write comments at the end of the line, just make sure it’s after the pipe operator %>%.

For example, these comments are allowed:

m_dose %>%# a comment here is fine# a comment here is finearrange(desc(weight_lost_g))

# A tibble: 344 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Black 6 3E 6.3 rep1 male 0.00221

2 Black 6 3E 6.05 rep1 male 0.0023

3 Black 6 3E 6 rep2 male 0.0022

4 Black 6 3E 6 rep3 male 0.00222

5 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep2 male 0.00223

6 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep3 male 0.00229

7 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep1 male 0.00213

8 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep1 male 0.00217

9 Black 6 3E 5.85 rep3 male 0.0023

10 Black 6 3E 5.8 rep2 male 0.00229

# ℹ 334 more rows

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

But this will cause an error, because the # is before the pipe, so R treats it as part of the comment (notice how the %>% has changed colour?) and doesn’t know how the two lines relate to each other. It tries to run them separately, which for the first line is ok (it will just print m_dose):

But for the second line, there is an error that R doesn’t know what the weight_lost_g object is. That’s because it’s a column in the m_dose data frame, so R only knows what it is in the context of the pipe chain containing that data frame.

You can also sort by multiple columns by passing multiple column names to arrange(). For example, to sort by the strain first and then by the amount of weight lost:

# sort by strain first, then by weight lostm_dose %>%arrange(mouse_strain, weight_lost_g)

# A tibble: 344 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 BALB C 2B 2.7 rep2 female 0.00192

2 BALB C 2B 2.9 rep1 female 0.00187

3 BALB C 2B 3.2 rep2 female 0.00187

4 BALB C 2B 3.25 rep1 female 0.00178

5 BALB C 2B 3.25 rep3 male 0.00187

6 BALB C 2B 3.25 rep3 female 0.00191

7 BALB C 2B 3.3 rep1 male 0.00197

8 BALB C 2B 3.3 rep1 female 0.00195

9 BALB C 2B 3.32 rep3 female 0.00199

10 BALB C 2B 3.35 rep2 female 0.00187

# ℹ 334 more rows

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

This will sort the data frame by strain (according to alphabetical order, as it is a character column), and within each strain, they are then sorted by the amount of weight lost.

Piping into View()

In the above example, we sorted the data by strain and then by weight lost, but because there are so many mice in each strain, the preview shown in our console doesn’t allow us to see the full effect of the sorting.

One handy trick you can use with pipes is to add View() at the end of your chain to open the data in a separate window. Try running this code, and you’ll be able to scroll through the full dataset to check that the other mouse strains have also been sorted correctly:

# sort by strain first, then by weight lostm_dose %>%arrange(mouse_strain, weight_lost_g) %>%View()

This is a great way to check that your code has actually done what you intended!

2.2.1.1 Extracting rows with the smallest or largest values

Slice functions are used to select rows based on their position in the data frame. The slice_min() and slice_max() functions are particularly useful, because they allow you to select the rows with the smallest or largest values in a particular column.

This is equivalent to using arrange() followed by head(), but is more concise:

# get the 10 mice with the lowest drug dosem_dose %>%# slice_min() requires the column to sort by, and n = the number of rows to keepslice_min(drug_dose_g, n =10)

# A tibble: 13 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 CD-1 3E 3.15 rep1 female 0.00172

2 CD-1 3E 3.4 rep1 female 0.00174

3 CD-1 1A 3.45 rep3 female 0.00176

4 CD-1 2B 3.25 rep1 female 0.00178

5 CD-1 2B 3.9 rep1 male 0.00178

6 CD-1 2B 2.9 rep2 female 0.00178

7 BALB C 2B 3.25 rep1 female 0.00178

8 CD-1 2B 2.98 rep1 <NA> 0.00179

9 CD-1 1A 3.7 rep1 <NA> 0.0018

10 CD-1 3E 3.6 rep1 male 0.0018

11 CD-1 3E 3.8 rep1 male 0.0018

12 CD-1 3E 3.95 rep1 male 0.0018

13 CD-1 2B 3.55 rep1 female 0.0018

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

# get the top 5 mice that lost the most weightm_dose %>%# slice_max() has the same arguments as slice_min()slice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5)

# A tibble: 6 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Black 6 3E 6.3 rep1 male 0.00221

2 Black 6 3E 6.05 rep1 male 0.0023

3 Black 6 3E 6 rep2 male 0.0022

4 Black 6 3E 6 rep3 male 0.00222

5 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep2 male 0.00223

6 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep3 male 0.00229

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

But wait— neither of those pieces of code actually gave the number of rows we asked for! In the first example, we asked for the 10 mice with the lowest drug dose, but we got 13. And in the second example, we asked for the top 5 mice that lost the most weight, but we got 6. Why aren’t the slice_ functions behaving as expected?

If we take a look at the help page (type ?slice_min in the console), we learn that slice_min() and slice_max() have an argument called with_ties that is set to TRUE by default. If we want to make sure we only get the number of rows we asked for, we would have to set it to FALSE, like so:

# get the top 5 mice that lost the most weightm_dose %>%# no ties allowed!slice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5, with_ties =FALSE)

# A tibble: 5 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Black 6 3E 6.3 rep1 male 0.00221

2 Black 6 3E 6.05 rep1 male 0.0023

3 Black 6 3E 6 rep2 male 0.0022

4 Black 6 3E 6 rep3 male 0.00222

5 Black 6 3E 5.95 rep2 male 0.00223

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

This is an important lesson: sometimes functions will behave in a way that is unexpected, and you might need to read their help page or use other guides/google/AI to understand why.

Practice exercises

Try these practice questions to test your understanding

1. Which code would you use to sort the m_dose data frame from biggest to smallest initial weight?

✗m_dose %>% sort(initial_weight_g)

✗m_dose %>% arrange(initial_weight_g)

✗m_dose %>% sort(descending(initial_weight_g))

✔m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g))

2. Which code would you use to extract the 3 mice with the highest initial weight from the m_dose data frame?

✔m_dose %>% slice_max(initial_weight_g, n = 3)

✗m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g))

✗m_dose %>% slice_min(initial_weight_g, n = 3)

✗m_dose %>% arrange(initial_weight_g)

3. I’ve written the below code, but one of the comments is messing it up! Which one?

# comment Am_dose # comment B %>%# comment Cslice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5, with_ties =FALSE) # comment D

✗Comment A

✔Comment B

✗Comment C

✗Comment D

Solutions

The correct code to sort the m_dose data frame from biggest to smallest initial weight is m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g)). The arrange() function is used to sort the data frame (although there is a sort() function in R, that’s not part of dplyr and won’t work the same way), and the desc() function is used to sort in descending order.

The correct code to extract the 3 mice with the highest initial weight from the m_dose data frame is m_dose %>% slice_max(initial_weight_g, n = 3). The slice_max() function is used to select the rows with the largest values in the initial_weight_g column, and the n = 3 argument specifies that we want to keep 3 rows. The arrange() function is not needed in this case, because slice_max() will automatically sort the data frame by the specified column.

The comment that is messing up the code is Comment B. The # symbol is before the pipe operator %>%, so R treats it as part of the comment and this breaks our chain of pipes. The other comments are fine, because they are either at the end of the line or on their own line. Basically, if a comment is changing the colour of the pipe operator (or any other bits of your code), it’s in the wrong place!

2.2.2 Filtering data (rows)

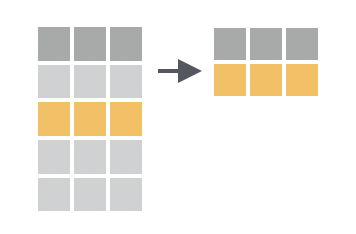

Filter allows you to filter rows using a logical test

In dplyr, the filter() function is used to subset rows based on their values. You provide a logical test, and filter() will keep the rows where the test is TRUE. We can write these tests using the comparison operators we learned in the previous chapter (e.g. ==, < and !=, see Section 1.3).

For example, to filter the m_dose data frame to only include mice that lost more than 6g:

m_dose %>%filter(weight_lost_g >6)

# A tibble: 2 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Black 6 3E 6.3 rep1 male 0.00221

2 Black 6 3E 6.05 rep1 male 0.0023

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

Or to only include mice from cage 3E:

m_dose %>%# remember that == is used for testing equalityfilter(cage_number =="3E") # don't forget the quotes either!

# A tibble: 168 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 CD-1 3E 3.4 rep1 female 0.00174

2 CD-1 3E 3.6 rep1 male 0.0018

3 CD-1 3E 3.8 rep1 female 0.00189

4 CD-1 3E 3.95 rep1 male 0.00185

5 CD-1 3E 3.8 rep1 male 0.0018

6 CD-1 3E 3.8 rep1 female 0.00187

7 CD-1 3E 3.55 rep1 male 0.00183

8 CD-1 3E 3.2 rep1 female 0.00187

9 CD-1 3E 3.15 rep1 female 0.00172

10 CD-1 3E 3.95 rep1 male 0.0018

# ℹ 158 more rows

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

2.2.2.1 Combining logical tests

Sometimes we want to filter based on multiple conditions. Here we will show some more advanced operators that can be used to combine logical tests.

The & operator is used to combine two logical tests with an ‘and’ condition. For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice that have a tail length greater than 19mm and are female:

m_dose %>%filter(tail_length_mm >19& sex =="female")

The | operator is used to combine two logical tests with an ‘or’ condition. For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice that have an initial weight less than 35g or a tail length less than 14mm:

The %in% operator can be used to filter based on a vector of multiple values (c(x, y)). It’s particularly useful when you have a few character values you want to filter on, as it is shorter to type than | (or).

For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice from cages 3E or 1A, we could use | like this:

✗Filters the data frame to remove mice from the “BALB C” and “Black 6” strains, who only lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose.

✗Filters the data frame to remove mice from the “BALB C” and “Black 6” strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.

✗Filters the data frame to only include mice from the “BALB C” and “Black 6” strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose.

✔Filters the data frame to only include mice from the “BALB C” and “Black 6” strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.

Solutions

The correct code to filter the m_dose data frame to only include mice from replicate 2 is m_dose %>% filter(replicate == "rep2"). Option A is incorrect because 2 is not a value of replicate (when filtering you need to know what values are actually in your columns! So make sure to View() your data first). Option B is incorrect because the replicate column is a character column, so you need to use quotes around the value you are filtering on. Option D is incorrect because = is not the correct way to test for equality, you need to use ==.

The invalid option is m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4) %>% (initial_weight_g < 40). This is because the second filtering step is missing the name of the filter function, so R doesn’t know what to do with (initial_weight_g < 40). The other options are valid ways to filter the data frame based on the specified conditions; note that we can use multiple filter() functions in a row to apply multiple conditions, or the & operator to combine them into a single filter() function. It’s just a matter of personal preference.

The correct description of the code is that it filters the data frame to only include mice from the “BALB C” and “Black 6” strains, then filters those further to only those that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and finally sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.

2.2.3 Dealing with missing values

Missing values are a common problem in real-world datasets. In R, missing values are represented by NA. In fact, if you look at the m_dose data frame we’ve been using, you’ll see that some of the cells contain NA: try spotting them with the View() function.

You can also find missing values in a data frame using the is.na() function in combination with filter(). For example, to find all the rows in the m_dose data frame that have a missing value for the drug_dose_g column:

m_dose %>%filter(is.na(drug_dose_g))

# A tibble: 2 × 9

mouse_strain cage_number weight_lost_g replicate sex drug_dose_g

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 CD-1 1A NA rep1 <NA> NA

2 Black 6 3E NA rep3 <NA> NA

# ℹ 3 more variables: tail_length_mm <dbl>, initial_weight_g <dbl>,

# id_num <dbl>

The problem with missing values is that they can cause problems when you try to perform calculations on your data. For example, if you try to calculate the mean of a column that contains even a single missing value, the result will also be NA:

# try to calculate the mean of the drug_dose_g column# remember from chapter 1 that we can use $ to access columns in a data framem_dose$drug_dose_g %>%mean()

[1] NA

NA values in R are therefore referred to as ‘contagious’: if you put an NA in you usually get an NA out. If you think about it, that makes sense— when we don’t know the value of a particular mouse’s drug dose, how can we calculate the average? That missing value could be anything.

For this reason, it’s important to deal with missing values before performing calculations. Many functions in R will have an argument called na.rm that you can set to TRUE to remove missing values before performing the calculation. For example, to calculate the mean of the drug_dose_g column with the missing values excluded:

# try to calculate the mean of the drug_dose_g column# remember from chapter 1 that we can use $ to access columns in a data framem_dose$drug_dose_g %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)

[1] 0.002009152

This time, the result is a number, because the missing values have been removed before the calculation.

But not all functions have an na.rm argument. In these cases, you can remove rows with missing values. This can be done for a single column, using the filter() function together with is.na():

# remove rows with missing values in the drug_dose_g columnm_dose %>%# remember the ! means 'not', it negates the result of is.na()filter(!is.na(drug_dose_g))

Sometimes, instead of removing rows with missing values, you might want to replace them with a specific value. This can be done using the replace_na() function from the tidyr package. replace_na() takes a list() which contains each of the column names you want to edit, and the value that should be used.

For example, to replace missing values in the weight_lost_g columns with 0, replace missing values in the sex column with ‘unknown’ and leave the rest of the data frame unchanged:

# replace missing values in the drug_dose_g column with 0m_dose %>%# here we need to provide the column_names = values_to_replace# this needs to be contained within a list()replace_na(list(weight_lost_g =0, sex ="unknown"))

When deciding how to handle missing values, you might have prior knowledge that NA should be replaced with a specific value, or you might decide that removing rows with NA is the best approach for your analysis.

For example, maybe we knew that the mice were given a weight_lost_g of NA if they didn’t lose any weight, it would then make sense to replace those with 0 (as we did in the code above). However, if the drug_dose_g column was missing simply because the data was lost, we might choose to remove those rows entirely.

It’s important to think carefully about how missing values should be handled in your analysis.

Practice exercises

Try these practice questions to test your understanding

1. What would be the result of running this R code: mean(c(1, 2, 4, NA))

✗2.333333

✗0

✔NA

✗An error

2. Which line of code would you use to filter the m_dose data frame to remove mice that have a missing value in the tail_length_mm column?

✗m_dose %>% filter(tail_length_mm != NA)

✗m_dose %>% filter(is.na(tail_length_mm))

✗m_dose %>% na.omit()

✔m_dose %>% filter(!is.na(tail_length_mm))

3. How would you replace missing values in the initial_weight_g column with the value 35?

The result of running the code mean(c(1, 2, 4, NA)) is NA. This is because the NA value is ‘contagious’, so when you try to calculate the mean of a vector that contains an NA, the result will also be NA. If we wanted to calculate the mean of the vector without the NA, we would need to use the na.rm = TRUE argument.

The correct line of code to filter the m_dose data frame to remove mice that have a missing value in the tail_length_mm column is m_dose %>% filter(!is.na(tail_length_mm)). The ! symbol is used to negate the result of is.na(), so we are filtering to keep the rows where tail_length_mm is not NA. We can’t use the first option with the != NA because NA is a special value in R that represents missing data, and it can’t be compared to anything, and the third option is incorrect because na.omit() removes entire rows with missing values, rather than just filtering based on a single column.

The correct line of code to replace missing values in the initial_weight_g column with the value 35 is m_dose %>% replace_na(list(initial_weight_g = 35)). The replace_na() function takes a list() that contains the column names you want to replace and the values you want to replace them with. We only need to use a single equal sign here as we’re not testing for equality, we’re assigning a value.

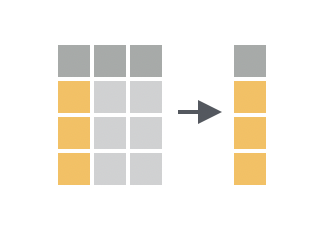

2.2.4 Selecting columns

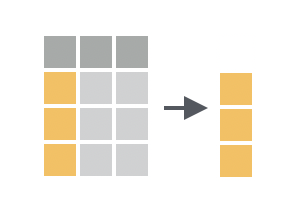

Select allows you to select only certain columns

While filter() is used to subset rows, select() is used to subset columns. You can use select() to keep only the columns you’re interested in, or to drop columns you don’t need.

The select() function takes the names of the columns that you want to keep/remove (no vector notation c() or quotation marks "" necessary). For example, to select only the mouse_strain, initial_weight_g, and weight_lost_g columns from the m_dose data frame:

There are also some helper functions that can be used to select columns based on their names :

There are several helper functions that can be used with the select function

Function

Description

Example

starts_with()

select column(s) that start with a certain string

select all columns starting with the letter i

select(starts_with("i"))

ends_with()

select column(s) that end with a certain string

select all columns ending with _g

select(ends_with("_g"))

contains()

select column(s) that contain a certain string

select all columns containing the word ‘weight’

select(contains("weight"))

You need to use quotation marks around the arguments in these helper functions, as they aren’t full column names, just strings of characters.

Try using these helper functions to select columns from the m_dose data frame!

Reordering columns

Relocate allows you to move columns around

We can reorder columns using the relocate() function, which works similarly to select() (except it just moves columns around rather than dropping/keeping them). For example, to move the sex column to before the cage_number column:

m_dose %>%# first the name of the column to move, then where it should gorelocate(sex, .before = cage_number)

Without a specific position ( .before / .after), this function will place the chosen column(s) as the first / left-most columns.

Two further useful helper functions for relocate() are the everything() and last_col() functions, which can be used to move columns to the start/end of the data frame.

# move id_num to the frontm_dose %>%relocate(id_num, .before =everything()) # don't forget the brackets

Re-ordering columns isn’t necessary, but it makes it easier to see the data you’re most interested in within the console (since often not all of the columns will fit on the screen at once). For example, if we are doing a lot of computation on the initial_weight_g column, we’d probably like to have that near the start so we can easily check it.

Note that the output of the select() function is a new data frame, even if you only select a single column:

# select the mouse_strain columnm_dose %>%select(mouse_strain) %>%# recall from chapter 1 that class() tells us the type of an objectclass()

[1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame"

Sometimes, we instead want to get the values of a column as a vector.

Pull allows you to pull a column out of a data frame as a vector

We can do this by using the pull() function, which extracts a single column from a data frame as a vector:

# get the mouse_strain column as a vectorm_dose %>%pull(mouse_strain) %>%class()

[1] "character"

We can see that the class of the output is now a vector, rather than a data frame. This is important because some functions only accept vectors, not data frames, like mean() for example:

# this will give an errorm_dose %>%select(initial_weight_g) %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)

Warning in mean.default(., na.rm = TRUE): argument is not numeric or logical:

returning NA

[1] NA

# this will workm_dose %>%pull(initial_weight_g) %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)

[1] 43.92193

Note how both times we used na.rm = TRUE to remove missing values before calculating the mean.

You might remember that we used the $ operator in the previous chapter to extract a single column from a data frame, so why use pull() instead? The main reason is that pull() works within a chain of pipes, whereas $ doesn’t.

For example, let’s say we want to know the average initial weight of mice that lost at least 4g. We can do this by chaining filter() and pull() together:

m_dose %>%# filter to mice that lost at least 4gfilter(weight_lost_g >=4) %>%# get the initial_weight_g column as a vectorpull(initial_weight_g) %>%# calculate mean, removing NA valuesmean(na.rm =TRUE)

[1] 46.48023

Practice exercises

Try these practice questions to test your understanding

1. Which line of code would NOT be a valid way to select only the drug_dose_g, initial_weight_g, and weight_lost_g columns from the m_dose data frame?

2. How would I extract the initial_weight_g column from the m_dose data frame as a vector?

✗m_dose %>% filter(initial_weight_g)

✗m_dose %>% $initial_weight_g

✗m_dose %>% select(initial_weight_g)

✔m_dose %>% pull(initial_weight_g)

3. How would you move the sex column to the end of the m_dose data frame?

✗m_dose %>% relocate(sex)

✗m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col)

✔m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col())

✗m_dose %>% reorder(sex, .after = last_col())

Solutions

The line of code that would NOT be a valid way to select the drug_dose_g, initial_weight_g, and weight_lost_g columns from the m_dose data frame is m_dose %>% select(contains("g")). This line of code would select all columns that contain the letter ‘g’, which would include columns like cage_number and tail_length_mm. We need to specify either ends_with("g") or contains("_g") to only get those with _g at the end. The other options are valid ways to select the specified columns, although some are more efficient than others!

The correct way to extract the initial_weight_g column from the m_dose data frame as a vector is m_dose %>% pull(initial_weight_g). The pull() function is used to extract a single column from a data frame as a vector. The other options are incorrect because filter() is used to subset rows, $ is not used in a pipe chain, and select() is outputs a data frame, not extract them as vectors.

The correct way to move the sex column to the end of the m_dose data frame is using the relocate() function like this: m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col()). The last_col() function is used to refer to the last column in the data frame. The other options are incorrect because reorder() is not a valid function, and you need to remember to include the brackets () when using last_col().

2.3 Summary

Here’s what we’ve covered in this chapter:

The pipe operator %>% and how we can use it to chain together multiple function calls, making our code more readable and easier to understand.

The basic dplyr verbs arrange(), filter() and select()

Why does data need to be tidy anyway?

In this chapter, we’ve been focusing on making our data ‘tidy’: that is, structured in a consistent way that makes it easy to work with. A nice visual illustration of tidy data and its importance can be found here.

2.3.1 Practice questions

What is the purpose of the pipe operator %>%? Keeping this in mind, re-write the following code to use the pipe.

round(mean(c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)))

print(as.character(1 + 10))

What would be the result of evaluating the following expressions? You don’t need to know these off the top of your head, use R to help! (Hint: some expressions might give an error. Try to think about why)

What is a missing value in R? What are two ways to deal with missing values in a data frame?

Solutions

The pipe operator %>% is used to chain together multiple function calls, passing the result of one function to the next. Here’s how you could re-write the code to use the pipe:

c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) %>% mean() %>% round()

as.character(1 + 10) %>% print()

The result of evaluating the expressions would be:

A data frame containing only the rows where weight_lost_g is greater than 10.

A data frame containing only the tail_length_mm and weight_lost_g columns.

A data frame sorted by tail_length_mm, in ascending order.

An error because initial_Weight_g is not a column in the data frame.

A data frame with the mouse_strain column moved to be after the cage_number column.

A vector containing the values of the weight_lost_g column.

A data frame containing only the rows where weight_lost_g is not NA.

A data frame with missing values in the weight_lost_g column replaced with 0.

A missing value in R is represented by NA. Two ways to deal with missing values in a data frame are to remove them using filter(!is.na(column_name)) or to replace them with a specific value using replace_na(list(column_name = value)).

---filters: - naquizformat: html: toc: true toc-location: left toc-title: "In this chapter:"---# Working with data - Part 1 {#sec-chapter02}In this chapter we will learn how to manipulate and summarise data using the `dplyr` package (with a little help from the `tidyr` package too).::: {.callout-tip title="Learning Objectives"}At the end of this chapter, learners should be able to:1. Use the pipe (`%>%`) to chain multiple functions together2. Design chains of dplyr functions to manipulate data frames3. Understand how to identify and handle missing values in a data frame:::Both `dplyr` and `tidyr` are contained within the `tidyverse` (along with `readr`) so we can load all of these packages at once using `library(tidyverse)`:```{r}# don't forget to load tidyverse!library(tidyverse)```## Chaining functions together with pipes {#sec-pipes}Pipes are a powerful feature of the `tidyverse` that allow you to chain multiple functions together.Pipes are useful because they allow you to break down complex operations into smaller steps that are easier to read and understand.For example, take the following code:```{r}my_vector <-c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)as.character(round(mean(my_vector)))```What do you think this code does?It calculates the mean of `my_vector`, rounds the result to the nearest whole number, and then converts the result to a character.But the code is a bit hard to read because you have to start from the inside of the brackets and work your way out.Instead, we can use the pipe operator (`%>%`) to chain these functions together in a more readable way:```{r}my_vector <-1:5my_vector %>%mean() %>%round() %>%as.character()```See how the code reads naturally from left to right?You can think of the pipe as being like the phrase "and then".Here, we're telling R: "Take `my_vector`, and then calculate the mean, and then round the result, and then convert it to a character."You'll notice that we didn't need to specify the input to each function.That's because the pipe automatically passes the output of the previous function as the first input to the next function.We can still specify additional arguments to each function if we need to.For example, if we wanted to round the mean to 2 decimal places, we could do this:```{r}my_vector %>%mean() %>%round(digits =2) %>%as.character()```R is clever enough to know that the first argument to `round()` is still the output of `mean()`, even though we've now specified the `digits` argument.::: {.callout-note title="Plenty of pipes"}There is another style of pipe in R, called the 'base R pipe' `|>`, which is available in R version 4.1.0 and later.The base R pipe works in a similar way to the `magrittr` pipe (`%>%`) that we use in this course, but it is not as flexible.We recommend using the `magrittr` pipe for now.Fun fact: the `magrittr` package is named after the [artist René Magritte, who made a famous painting of a pipe](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images).:::To type the pipe operator more easily, you can use the keyboard shortcut {{< kbd Cmd-shift-M >}} (although once you get used to it, you might find it easier to type `%>%` manually).::::::::::::::: {.callout-important title="Practice exercises"}Try these practice questions to test your understanding:::::::: question1\.What is NOT a valid way to re-write the following code using the pipe operator: `round(sqrt(sum(1:10)), 1)`.If you're not sure, try running the different options in the console to see which one gives the same answer.::::::: choices::: choice`1:10 %>% sum() %>% sqrt() %>% round(1)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`sum(1:10) %>% sqrt(1) %>% round()`:::::: choice`1:10 %>% sum() %>% sqrt() %>% round(digits = 1)`:::::: choice`sum(1:10) %>% sqrt() %>% round(digits = 1)`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question2\.What is the output of the following code?`letters %>% head() %>% toupper()` Try to guess it before copy-pasting into R.::::::: choices::: choice`"A" "B" "C" "D" "E" "F" "G" "H" "I" "J" "K" "L" "M" "N" "O" "P" "Q" "R" "S" "T" "U" "V" "W" "X" "Y" "Z"`:::::: choice`"a" "b" "c" "d" "e" "f"`:::::: choiceAn error:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`"A" "B" "C" "D" "E" "F"`::::::::::::::::::<details><summary>Solutions</summary><p>1. The invalid option is `sum(1:10) %>% sqrt(1) %>% round()`. This is because the `sqrt()` function only takes one argument, so you can't specify `1` as an argument in addition to what is being piped in from `sum(1:10)`. Note that some options used the pipe to send `1:10` to `sum()` (like `1:10 %>% sum()`), and others just used `sum(1:10)` directly. Both are valid ways to use the pipe, it's just a matter of personal preference.2. The output of the code `letters %>% head() %>% toupper()` is `"A" "B" "C" "D" "E" "F"`. The `letters` vector contains the lowercase alphabet, and the `head()` function returns the first 6 elements of the vector. Finally, the `toupper()` function then converts these elements to uppercase.</p></details>:::::::::::::::## Basic data manipulation {#sec-dataManip}To really see the power of the pipe, we will use it together with the `dplyr` package that provides a set of functions to easily filter, sort, select, modify and summarise data frames.These functions are designed to work well with the pipe, so you can chain them together to create complex data manipulations in a readable format.For example, even though we haven't covered the `dplyr` functions yet, you can probably guess what the following code does:```{r}#| eval: false# use the pipe to chain together our data manipulation stepsm_dose %>%filter(cage_number =="3E") %>%drop_na(weight_lost_g) %>%pull(weight_lost_g) %>%mean()```This code filters the `m_dose` data frame to only include data from cage 3E, then pulls out the `weight_lost_g` column, and finally calculates the mean of the values in that column.The first argument to each function is the output of the previous function, and any additional arguments (like the column name in `pull()`) are specified in the brackets (like `round(digits = 2)` from the previous example).We also used the enter key after each pipe `%>%` to break up the code into multiple lines to make it easier to read.This isn't required, but is a popular style in the R community, so all the code examples in this chapter will follow this format.We will now introduce some of the most commonly used `dplyr` functions for manipulating data frames.To showcase these, we will use the `m_dose` that we practiced reading in last chapter.This imaginary dataset contains information on the weight lost by different strains of mice after being treated with different doses of MouseZempic®.```{r}#| eval: false# read in the data, like we did in chapter 1m_dose <-read_delim("data/mousezempic_dosage_data.csv")``````{r}#| echo: false# just for rendering the book not for students to seem_dose <-read_delim("data/mousezempic_dosage_data.csv")```Before we start, let's use what we learned in the previous chapter to take a look at `m_dose`:```{r}# it's a tibble, so prints nicelym_dose```You might also like to use `View()` to open the data in a separate window and get a closer look.::: {.callout-note title="Using RStudio autocomplete"}Although it's great to give our data a descriptive name like `m_dose`, it can be a bit of a pain to type out every time.Luckily, RStudio has a handy autocomplete feature that can solve this problem.Just start typing the name of the object, and you'll see it will popup:You can then press {{< kbd Tab >}} to autocomplete it.If there are multiple objects that start with the same letters, you can use the arrow keys to cycle through the options.Try using autocomplete in this chapter to save yourself some typing!:::### Sorting data {#sec-sorting}Often, one of the first things you might want to do with a dataset is sort it.In `dplyr`, this is called 'arranging' and is done with the `arrange()` function.By default, `arrange()` sorts in ascending order (smallest values first).For example, let's sort the `m_dose` data frame by the `weight_lost_g` column:```{r}m_dose %>%arrange(weight_lost_g)```If we compare this to when we just printed our data above, we can see that the rows are now sorted so that the mice that lost the least weight are at the top.Sometimes you might want to sort in descending order instead (largest values first).You can do this by putting the `desc()` function around your column name, inside `arrange()`:```{r}m_dose %>%# put desc() around the column name to sort in descending orderarrange(desc(weight_lost_g))```Now we can see the mice that lost the most weight are at the top.::: {.callout-note title="Comments and pipes"}Notice how in the previous example we have written a comment in the middle of the pipe chain.This is a good practice to help you remember what each step is doing, especially when you have a long chain of functions, and won't cause any errors as long as you make sure that the comment is on its own line.You can also write comments at the end of the line, just make sure it's after the pipe operator `%>%`.For example, these comments are allowed:```{r}m_dose %>%# a comment here is fine# a comment here is finearrange(desc(weight_lost_g))```But this will cause an error, because the `#` is before the pipe, so R treats it as part of the comment (notice how the `%>%` has changed colour?) and doesn't know how the two lines relate to each other.It tries to run them separately, which for the first line is ok (it will just print `m_dose`):```{r}#| error: truem_dose # this comment will cause an error %>%arrange(desc(weight_lost_g))```But for the second line, there is an error that R doesn't know what the `weight_lost_g` object is.That's because it's a column in the `m_dose` data frame, so R only knows what it is in the context of the pipe chain containing that data frame.:::You can also sort by multiple columns by passing multiple column names to `arrange()`.For example, to sort by the strain first and then by the amount of weight lost:```{r}# sort by strain first, then by weight lostm_dose %>%arrange(mouse_strain, weight_lost_g)```This will sort the data frame by strain (according to alphabetical order, as it is a character column), and within each strain, they are then sorted by the amount of weight lost.::: {.callout-note title="Piping into View()"}In the above example, we sorted the data by strain and then by weight lost, but because there are so many mice in each strain, the preview shown in our console doesn't allow us to see the full effect of the sorting.One handy trick you can use with pipes is to add `View()` at the end of your chain to open the data in a separate window.Try running this code, and you'll be able to scroll through the full dataset to check that the other mouse strains have also been sorted correctly:```{r}#| eval: false# sort by strain first, then by weight lostm_dose %>%arrange(mouse_strain, weight_lost_g) %>%View()```This is a great way to check that your code has actually done what you intended!:::#### Extracting rows with the smallest or largest values {#sec-sliceMinMax}Slice functions are used to select rows based on their position in the data frame.The `slice_min()` and `slice_max()` functions are particularly useful, because they allow you to select the rows with the smallest or largest values in a particular column.This is equivalent to using `arrange()` followed by `head()`, but is more concise:```{r}# get the 10 mice with the lowest drug dosem_dose %>%# slice_min() requires the column to sort by, and n = the number of rows to keepslice_min(drug_dose_g, n =10)# get the top 5 mice that lost the most weightm_dose %>%# slice_max() has the same arguments as slice_min()slice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5)```But wait— neither of those pieces of code actually gave the number of rows we asked for!In the first example, we asked for the 10 mice with the lowest drug dose, but we got 13.And in the second example, we asked for the top 5 mice that lost the most weight, but we got 6.Why aren't the `slice_` functions behaving as expected?If we take a look at the help page (type `?slice_min` in the console), we learn that `slice_min()` and `slice_max()` have an argument called `with_ties` that is set to `TRUE` by default.If we want to make sure we only get the number of rows we asked for, we would have to set it to `FALSE`, like so:```{r}# get the top 5 mice that lost the most weightm_dose %>%# no ties allowed!slice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5, with_ties =FALSE)```This is an important lesson: sometimes functions will behave in a way that is unexpected, and you might need to read their help page or use other guides/google/AI to understand why.::::::::::::::::::::: {.callout-important title="Practice exercises"}Try these practice questions to test your understanding:::::::: question1\.Which code would you use to sort the `m_dose` data frame from biggest to smallest initial weight?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% sort(initial_weight_g)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% arrange(initial_weight_g)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% sort(descending(initial_weight_g))`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g))`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question2\.Which code would you use to extract the 3 mice with the highest initial weight from the `m_dose` data frame?::::::: choices::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% slice_max(initial_weight_g, n = 3)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% slice_min(initial_weight_g, n = 3)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% arrange(initial_weight_g)`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question3\.I've written the below code, but one of the comments is messing it up!Which one?```{r}#| eval: false# comment Am_dose # comment B %>%# comment Cslice_max(weight_lost_g, n =5, with_ties =FALSE) # comment D```::::::: choices::: choiceComment A:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}Comment B:::::: choiceComment C:::::: choiceComment D::::::::::::::::::<details><summary>Solutions</summary>1. The correct code to sort the `m_dose` data frame from biggest to smallest initial weight is `m_dose %>% arrange(desc(initial_weight_g))`. The `arrange()` function is used to sort the data frame (although there is a `sort()` function in R, that's not part of dplyr and won't work the same way), and the `desc()` function is used to sort in descending order.2. The correct code to extract the 3 mice with the highest initial weight from the `m_dose` data frame is `m_dose %>% slice_max(initial_weight_g, n = 3)`. The `slice_max()` function is used to select the rows with the largest values in the `initial_weight_g` column, and the `n = 3` argument specifies that we want to keep 3 rows. The `arrange()` function is not needed in this case, because `slice_max()` will automatically sort the data frame by the specified column.3. The comment that is messing up the code is Comment B. The `#` symbol is before the pipe operator `%>%`, so R treats it as part of the comment and this breaks our chain of pipes. The other comments are fine, because they are either at the end of the line or on their own line. Basically, if a comment is changing the colour of the pipe operator (or any other bits of your code), it's in the wrong place!</details>:::::::::::::::::::::### Filtering data (rows) {#sec-filter}In `dplyr`, the `filter()` function is used to subset rows based on their values.You provide a logical test, and `filter()` will keep the rows where the test is `TRUE`.We can write these tests using the comparison operators we learned in the previous chapter (e.g. `==`, `<` and `!=`, see [Section @sec-comparisons]).For example, to filter the `m_dose` data frame to only include mice that lost more than 6g:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(weight_lost_g >6)```Or to only include mice from cage 3E:```{r}m_dose %>%# remember that == is used for testing equalityfilter(cage_number =="3E") # don't forget the quotes either!```#### Combining logical testsSometimes we want to filter based on multiple conditions.Here we will show some more advanced operators that can be used to combine logical tests.The `&` operator is used to combine two logical tests with an 'and' condition.For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice that have a tail length greater than 19mm and are female:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(tail_length_mm >19& sex =="female")```The `|` operator is used to combine two logical tests with an 'or' condition.For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice that have an initial weight less than 35g or a tail length less than 14mm:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(initial_weight_g <35| tail_length_mm <14)```The `%in%` operator can be used to filter based on a vector of multiple values (`c(x, y)`).It's particularly useful when you have a few character values you want to filter on, as it is shorter to type than `|` (or).For example, to filter the data frame to only include mice from cages 3E or 1A, we could use `|` like this:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(cage_number =="3E"| cage_number =="1A")```Or we could use `%in%` like this:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(cage_number %in%c("3E", "1A"))```::::::::::::::::::::: {.callout-important title="Practice exercises"}Try these practice questions to test your understanding:::::::: question1\.Which code would you use to filter the `m_dose` data frame to only include mice from replicate 2?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(replicate == 2)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(replicate == rep2)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% filter(replicate == "rep2")`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(replicate = "rep2")`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question2\.What is NOT a valid way to filter the `m_dose` data frame to only include mice that lost more than 4g, and have an initial weight less than 40g?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4) %>% filter(initial_weight_g < 40)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4) %>% (initial_weight_g < 40)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4 & initial_weight_g < 40)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(initial_weight_g < 40) %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4)`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question3\.Which option correctly describes what the following code is doing?```{r}#| eval: falsem_dose %>%filter(mouse_strain %in%c("BALB C", "Black 6")) %>%filter(weight_lost_g >3& weight_lost_g <5) %>%arrange(desc(drug_dose_g))```::::::: choices::: choiceFilters the data frame to remove mice from the "BALB C" and "Black 6" strains, who only lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose.:::::: choiceFilters the data frame to remove mice from the "BALB C" and "Black 6" strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.:::::: choiceFilters the data frame to only include mice from the "BALB C" and "Black 6" strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose.:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}Filters the data frame to only include mice from the "BALB C" and "Black 6" strains, that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and then sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.::::::::::::::::::<details><summary>Solutions</summary>1. The correct code to filter the `m_dose` data frame to only include mice from replicate 2 is `m_dose %>% filter(replicate == "rep2")`. Option A is incorrect because `2` is not a value of `replicate` (when filtering you need to know what values are actually in your columns! So make sure to `View()` your data first). Option B is incorrect because the replicate column is a character column, so you need to use quotes around the value you are filtering on. Option D is incorrect because `=` is not the correct way to test for equality, you need to use `==`.2. The invalid option is `m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 4) %>% (initial_weight_g < 40)`. This is because the second filtering step is missing the name of the filter function, so R doesn't know what to do with `(initial_weight_g < 40)`. The other options are valid ways to filter the data frame based on the specified conditions; note that we can use multiple `filter()` functions in a row to apply multiple conditions, or the `&` operator to combine them into a single `filter()` function. It's just a matter of personal preference.3. The correct description of the code is that it filters the data frame to only include mice from the "BALB C" and "Black 6" strains, then filters those further to only those that lost between 3 and 5g of weight, and finally sorts the data frame by drug dose in descending order.</details>:::::::::::::::::::::### Dealing with missing values {#sec-missing}Missing values are a common problem in real-world datasets.In R, missing values are represented by `NA`.In fact, if you look at the `m_dose` data frame we've been using, you'll see that some of the cells contain `NA`: try spotting them with the `View()` function.You can also find missing values in a data frame using the `is.na()` function in combination with `filter()`.For example, to find all the rows in the `m_dose` data frame that have a missing value for the `drug_dose_g` column:```{r}m_dose %>%filter(is.na(drug_dose_g))```The problem with missing values is that they can cause problems when you try to perform calculations on your data.For example, if you try to calculate the mean of a column that contains even a single missing value, the result will also be `NA`:```{r}# try to calculate the mean of the drug_dose_g column# remember from chapter 1 that we can use $ to access columns in a data framem_dose$drug_dose_g %>%mean()````NA` values in R are therefore referred to as 'contagious': if you put an `NA` in you usually get an `NA` out.If you think about it, that makes sense— when we don't know the value of a particular mouse's drug dose, how can we calculate the average?That missing value could be anything.For this reason, it's important to deal with missing values before performing calculations.Many functions in R will have an argument called `na.rm` that you can set to `TRUE` to remove missing values before performing the calculation.For example, to calculate the mean of the `drug_dose_g` column with the missing values excluded:```{r}# try to calculate the mean of the drug_dose_g column# remember from chapter 1 that we can use $ to access columns in a data framem_dose$drug_dose_g %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)```This time, the result is a number, because the missing values have been removed before the calculation.But not all functions have an `na.rm` argument.In these cases, you can remove rows with missing values.This can be done for a single column, using the `filter()` function together with `is.na()`:```{r}# remove rows with missing values in the drug_dose_g columnm_dose %>%# remember the ! means 'not', it negates the result of is.na()filter(!is.na(drug_dose_g))```Or, you can remove rows with missing values in any column using the `na.omit()` or `drop_na()` function:```{r}# remove rows with missing values in any columnm_dose %>%na.omit()m_dose %>%drop_na()```Sometimes, instead of removing rows with missing values, you might want to replace them with a specific value.This can be done using the `replace_na()` function from the `tidyr` package.`replace_na()` takes a `list()` which contains each of the column names you want to edit, and the value that should be used.For example, to replace missing values in the `weight_lost_g` columns with 0, replace missing values in the `sex` column with 'unknown' and leave the rest of the data frame unchanged:```{r}# replace missing values in the drug_dose_g column with 0m_dose %>%# here we need to provide the column_names = values_to_replace# this needs to be contained within a list()replace_na(list(weight_lost_g =0, sex ="unknown"))```When deciding how to handle missing values, you might have prior knowledge that `NA` should be replaced with a specific value, or you might decide that removing rows with `NA` is the best approach for your analysis.For example, maybe we knew that the mice were given a `weight_lost_g` of `NA` if they didn't lose any weight, it would then make sense to replace those with 0 (as we did in the code above).However, if the `drug_dose_g` column was missing simply because the data was lost, we might choose to remove those rows entirely.It's important to think carefully about how missing values should be handled in your analysis.::::::::::::::::::::: {.callout-important title="Practice exercises"}Try these practice questions to test your understanding:::::::: question1\.What would be the result of running this R code: `mean(c(1, 2, 4, NA))`::::::: choices::: choice2.333333:::::: choice0:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`NA`:::::: choiceAn error:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question2\.Which line of code would you use to filter the `m_dose` data frame to remove mice that have a missing value in the `tail_length_mm` column?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(tail_length_mm != NA)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(is.na(tail_length_mm))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% na.omit()`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% filter(!is.na(tail_length_mm))`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question3\.How would you replace missing values in the `initial_weight_g` column with the value 35?::::::: choices::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% replace_na(list(initial_weight_g = 35))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% replace_na(initial_weight_g = 35)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% replace_na(list(initial_weight_g == 35))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% replace_na(35)`::::::::::::::::::<details><summary>Solutions</summary><p>1. The result of running the code `mean(c(1, 2, 4, NA))` is `NA`. This is because the `NA` value is 'contagious', so when you try to calculate the mean of a vector that contains an `NA`, the result will also be `NA`. If we wanted to calculate the mean of the vector without the `NA`, we would need to use the `na.rm = TRUE` argument.2. The correct line of code to filter the `m_dose` data frame to remove mice that have a missing value in the `tail_length_mm` column is `m_dose %>% filter(!is.na(tail_length_mm))`. The `!` symbol is used to negate the result of `is.na()`, so we are filtering to keep the rows where `tail_length_mm` is not `NA`. We can't use the first option with the `!= NA` because `NA` is a special value in R that represents missing data, and it can't be compared to anything, and the third option is incorrect because `na.omit()` removes entire rows with missing values, rather than just filtering based on a single column.3. The correct line of code to replace missing values in the `initial_weight_g` column with the value 35 is `m_dose %>% replace_na(list(initial_weight_g = 35))`. The `replace_na()` function takes a `list()` that contains the column names you want to replace and the values you want to replace them with. We only need to use a single equal sign here as we're not testing for equality, we're assigning a value.</p></details>:::::::::::::::::::::### Selecting columns {#sec-select}While `filter()` is used to subset rows, `select()` is used to subset columns.You can use `select()` to keep only the columns you're interested in, or to drop columns you don't need.The `select()` function takes the names of the columns that you want to keep/remove (no vector notation `c()` or quotation marks `""` necessary).For example, to select only the `mouse_strain`, `initial_weight_g`, and `weight_lost_g` columns from the `m_dose` data frame:```{r}m_dose %>%select(mouse_strain, initial_weight_g, weight_lost_g)```We can see that all the other columns have been removed from the data frame.If you want to keep all columns except for a few, you can use `-` to drop columns.For example, to keep all columns except for `cage_number` and `sex`:```{r}m_dose %>%select(-cage_number, -sex)```There are also some helper functions that can be used to select columns based on their names :+-----------------+---------------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------------------+| Function | Description | Example |+=================+===================================================+=================================================+| `starts_with()` | select column(s) that start with a certain string | select all columns starting with the letter i || | | || | | `select(starts_with("i"))` |+-----------------+---------------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------------------+| `ends_with()` | select column(s) that end with a certain string | select all columns ending with \_g || | | || | | `select(ends_with("_g"))` |+-----------------+---------------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------------------+| `contains()` | select column(s) that contain a certain string | select all columns containing the word 'weight' || | | || | | `select(contains("weight"))` |+-----------------+---------------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------------------+: There are several helper functions that can be used with the select functionYou need to use quotation marks around the arguments in these helper functions, as they aren't full column names, just strings of characters.Try using these helper functions to select columns from the `m_dose` data frame!::: {.callout-note title="Reordering columns"}We can reorder columns using the `relocate()` function, which works similarly to `select()` (except it just moves columns around rather than dropping/keeping them).For example, to move the `sex` column to before the `cage_number` column:```{r}m_dose %>%# first the name of the column to move, then where it should gorelocate(sex, .before = cage_number)```Without a specific position `( .before / .after)`, this function will place the chosen column(s) as the first / left-most columns.Two further useful helper functions for `relocate()` are the `everything()` and `last_col()` functions, which can be used to move columns to the start/end of the data frame.```{r}# move id_num to the frontm_dose %>%relocate(id_num, .before =everything()) # don't forget the brackets# move mouse_strain to the endm_dose %>%relocate(mouse_strain, .after =last_col())```Re-ordering columns isn't necessary, but it makes it easier to see the data you're most interested in within the console (since often not all of the columns will fit on the screen at once).For example, if we are doing a lot of computation on the `initial_weight_g` column, we'd probably like to have that near the start so we can easily check it.:::Note that the output of the `select()` function is a new data frame, even if you only select a single column:```{r}# select the mouse_strain columnm_dose %>%select(mouse_strain) %>%# recall from chapter 1 that class() tells us the type of an objectclass()```Sometimes, we instead want to get the values of a column as a vector.We can do this by using the `pull()` function, which extracts a single column from a data frame as a vector:```{r}# get the mouse_strain column as a vectorm_dose %>%pull(mouse_strain) %>%class()```We can see that the class of the output is now a vector, rather than a data frame.This is important because some functions only accept vectors, not data frames, like `mean()` for example:```{r}# this will give an errorm_dose %>%select(initial_weight_g) %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)# this will workm_dose %>%pull(initial_weight_g) %>%mean(na.rm =TRUE)```Note how both times we used `na.rm = TRUE` to remove missing values before calculating the mean.You might remember that we used the `$` operator in the previous chapter to extract a single column from a data frame, so why use `pull()` instead?The main reason is that `pull()` works within a chain of pipes, whereas `$` doesn't.For example, let's say we want to know the average initial weight of mice that lost at least 4g.We can do this by chaining `filter()` and `pull()` together:```{r}m_dose %>%# filter to mice that lost at least 4gfilter(weight_lost_g >=4) %>%# get the initial_weight_g column as a vectorpull(initial_weight_g) %>%# calculate mean, removing NA valuesmean(na.rm =TRUE)```::::::::::::::::::::: {.callout-important title="Practice exercises"}Try these practice questions to test your understanding:::::::: question1\.Which line of code would NOT be a valid way to select only the `drug_dose_g`, `initial_weight_g`, and `weight_lost_g` columns from the `m_dose` data frame?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% select(drug_dose_g, initial_weight_g, weight_lost_g)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% select(contains("g"))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% select(ends_with("_g"))`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% select(-cage_number, -tail_length_mm, -id_num, -mouse_strain, -sex, -replicate)`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question2\.How would I extract the `initial_weight_g` column from the `m_dose` data frame as a vector?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% filter(initial_weight_g)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% $initial_weight_g`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% select(initial_weight_g)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% pull(initial_weight_g)`:::::::::::::::::::::::::: question3\.How would you move the `sex` column to the end of the `m_dose` data frame?::::::: choices::: choice`m_dose %>% relocate(sex)`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col)`:::::: {.choice .correct-choice}`m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col())`:::::: choice`m_dose %>% reorder(sex, .after = last_col())`::::::::::::::::::<details><summary>Solutions</summary><p>1. The line of code that would NOT be a valid way to select the `drug_dose_g`, `initial_weight_g`, and `weight_lost_g` columns from the `m_dose` data frame is `m_dose %>% select(contains("g"))`. This line of code would select all columns that contain the letter 'g', which would include columns like `cage_number` and `tail_length_mm`. We need to specify either `ends_with("g")` or `contains("_g")` to only get those with `_g` at the end. The other options are valid ways to select the specified columns, although some are more efficient than others!2. The correct way to extract the `initial_weight_g` column from the `m_dose` data frame as a vector is `m_dose %>% pull(initial_weight_g)`. The `pull()` function is used to extract a single column from a data frame as a vector. The other options are incorrect because `filter()` is used to subset rows, `$` is not used in a pipe chain, and `select()` is outputs a data frame, not extract them as vectors.3. The correct way to move the `sex` column to the end of the `m_dose` data frame is using the `relocate()` function like this: `m_dose %>% relocate(sex, .after = last_col())`. The `last_col()` function is used to refer to the last column in the data frame. The other options are incorrect because `reorder()` is not a valid function, and you need to remember to include the brackets `()` when using `last_col()`.</p></details>:::::::::::::::::::::## SummaryHere's what we've covered in this chapter:- The pipe operator `%>%` and how we can use it to chain together multiple function calls, making our code more readable and easier to understand.- The basic dplyr verbs `arrange()`, `filter()` and `select()`::: {.callout-note title="Why does data need to be tidy anyway?"}In this chapter, we've been focusing on making our data 'tidy': that is, structured in a consistent way that makes it easy to work with.A nice visual illustration of tidy data and its importance can be [found here](https://allisonhorst.com/other-r-fun).:::### Practice questions1. What is the purpose of the pipe operator `%>%`? Keeping this in mind, re-write the following code to use the pipe. a. `round(mean(c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)))` b. `print(as.character(1 + 10))`2. What would be the result of evaluating the following expressions? You don't need to know these off the top of your head, use R to help! (Hint: some expressions might give an error. Try to think about why) a. `m_dose %>% filter(weight_lost_g > 10)` b. `m_dose %>% select(tail_length_mm, weight_lost_g)` c. `m_dose %>% arrange(tail_length_mm)` d. `m_dose %>% filter(initial_Weight_g > 10) %>% arrange(mouse_strain)` e. `m_dose %>% relocate(mouse_strain, .after = cage_number)` f. `m_dose %>% pull(weight_lost_g)` g. `m_dose %>% filter(!is.na(weight_lost_g))` h. `m_dose %>% replace_na(list(weight_lost_g = 0))`3. What is a missing value in R? What are two ways to deal with missing values in a data frame?<details><summary>Solutions</summary>1. The pipe operator `%>%` is used to chain together multiple function calls, passing the result of one function to the next. Here's how you could re-write the code to use the pipe: a. `c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) %>% mean() %>% round()` b. `as.character(1 + 10) %>% print()`2. The result of evaluating the expressions would be: a. A data frame containing only the rows where `weight_lost_g` is greater than 10. b. A data frame containing only the `tail_length_mm` and `weight_lost_g` columns. c. A data frame sorted by `tail_length_mm`, in ascending order. d. An error because `initial_Weight_g` is not a column in the data frame. e. A data frame with the `mouse_strain` column moved to be after the `cage_number` column. f. A **vector** containing the values of the `weight_lost_g` column. g. A data frame containing only the rows where `weight_lost_g` is not `NA`. h. A data frame with missing values in the `weight_lost_g` column replaced with 0.3. A missing value in R is represented by `NA`. Two ways to deal with missing values in a data frame are to remove them using `filter(!is.na(column_name))` or to replace them with a specific value using `replace_na(list(column_name = value))`.</details>